Sixes Lacrosse: Defense & Transition Wins Championships

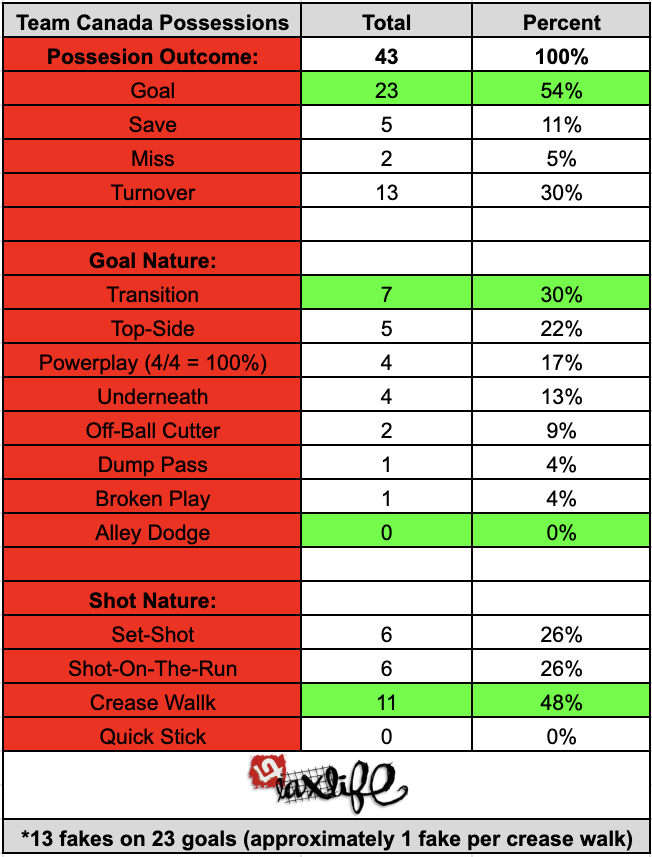

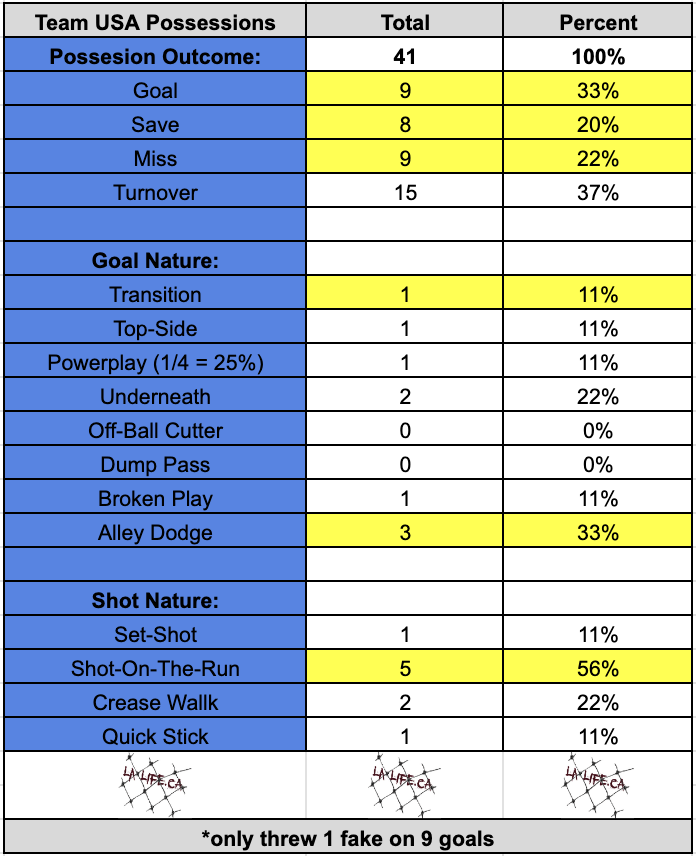

There is certainly a case in sixes lacrosse for the old adage “the best defense is a good offense” when you consider the 23-9 drubbing Canada put on the USA in the Gold medal game of the 2022 World Sixes Lacrosse Championship in Alabama, USA. However, the old saying “defense wins championships” also checks out and for me, combined with elite Defense to Offense transition, which was the secret sauce in the Canadian blow out in Alabama.

Defense starts as soon as you lose the ball and there were many times, including after a goal or a missed shot in a settled offense or a powerplay, where Canada and the US went into a 2-player or full field press depending on the situation. It was seemingly very effective when they did, as both teams were barely able to get a shot off by the time they got to the offensive end. The US threw up the first press 5-on-5 two minutes into the first quarter after a Dobson save - resulting in a turnover from Challen Rogers (although the Canadian coaches recognized he was in trouble and called a time out first so they got the ball back). Canada threw out the next press a minute later after Cole missed the net (5-on-5) on a shot. It took the USA 15 seconds to clear half and ended up with no time on offense and a turnover, with the American player having no option but to try to get to the net 1-on-2 with under 5 seconds remaining in the shot clock. All three 5-on-5 pressure situations resulted in turnovers, with Canada not allowing a shot on 3 out of 4 powerplay pressures and the USA not allowing a shot on 1 out of 2 (both shots allowed were short-handed goals that should have been saves in my opinion).

In saying that, most of the time Canada laid off the press and instinctively got back to defense, covering reverse-transition (which is their primary responsibility) and relying on their top notch defense and goaltending. The best defenses start and end with quality goaltending and Canada had no shortage of that at this tournament, with a 60% save percentage and 6 goal/game average posted by Brett Dobson (2023 PLL Championship Game MVP).

Quality goaltending is then reinforced with good foot and body positioning by the players in front of the goalie. “On-ball” positioning should be a few steps back to the middle, hips parallel to the side boards, in line with the offender’s top shoulder; between their stick and the net. The on-ball defender needs to stand in the “shooting lane,” willing to block a shot, trying to keep the shot in front of them not behind them (i.e. no screen shots - no screening the goalie).

This is all within the framework of what’s historically known as a “helping man-to-man” (player-to-player in gender neutral terms) defense. The key is to know when to “go” and when to “show” in terms of helping. "Off-ball" defenders should position themselves further away from their check, ready to help in the “prime scoring” area, also to stay “tight” as a unit. Off-ball and “adjacent” (same side) defenders need to “sag” over “showing help," but also be able to recover to their check if necessary. If a teammate gets beat towards the net then the next closest defender should “slide” over and help out, with other all defenders "helping the helper," if need be. The thought is that the offense has to beat all 5 defenders in order to score a goal; another analogy would be that you must cover 1.5 players at all times, your check and half of someone else's. The ultimate goal is not to get scored on, defending just your check isn’t good enough!

Once you’ve made the defensive stop and scooped the loose ball, players should run up-floor at full speed and "push the ball" up to any players ahead of them if possible. If a numerical player advantage (one or more player advantage) exists in transition, players should attempt to get to their proper floor side as early as possible and the aim of any fast-break scenario should be to break down a 4-on-3 into a 3-on-2, into a 2-on-1, and onto a breakaway, unless a quality shot in the prime scoring area presents itself first.

It’s worth noting that 2 out of the first 3 defensive sets were fast break goals for Currier, also that the first 3 offensive possessions from the Americans were outside shots and two of them “alley shots” (3 saves).

For the remainder of this blog I will break down 10 defensive shifts from the first quarter which were indicative of the outcome of the game, starting first with the first four from Canada.

Clip #1 (Canada - Defensive Set #1): “Currier Makes USA Pay In Transition”

In this first one, Canada is a little bit too spread out for my liking, much further out than they would be in traditional box lacrosse. This is probably due to the size of the net which makes the defenders have to push out a bit further to protect against a longer range uncontested outside shot. Regardless, usually we don’t push out to the low corners like this defensively, likely they’ve done this to try to take away the effectiveness of USA’s superior dodging ability early when they were fresh early in the game; also something that Canada stopped doing as the game progressed. In this case, #42 Petterson on Canada is lunging instead of sitting back in the chair as we say, which allows #13 Guterding on USA to swim him and drive hard underneath. This forces Cole (#55) to give the adjacent slide for support, at which point Guterding curls out and hits the adjacent pass (which USA should have done more of generally speaking), forcing the rest of the defense to “rotate” in order to recover.

Currier does a good job of having his head on a swivel and recognizing the situation, but unfortunately closes the gap on #2 Heacock's low shoulder when he slides, allowing him to get top-side. If Heacock steps into the this one instead of doing the jump shot he would have gotten closer to the net and might have scored and the stats also show that it should have been a bounce shot which ill show you in the next blog/vlog on "offense and special teams." Currier, knowing he was already beat, just took off “cheating/leaking” they other way which is a risk worth taking in that situation and it paid off because #22 Conrad was sleeping on the far-side and didn’t do his job as off-ball high player, who needs to cover reverse-transition.

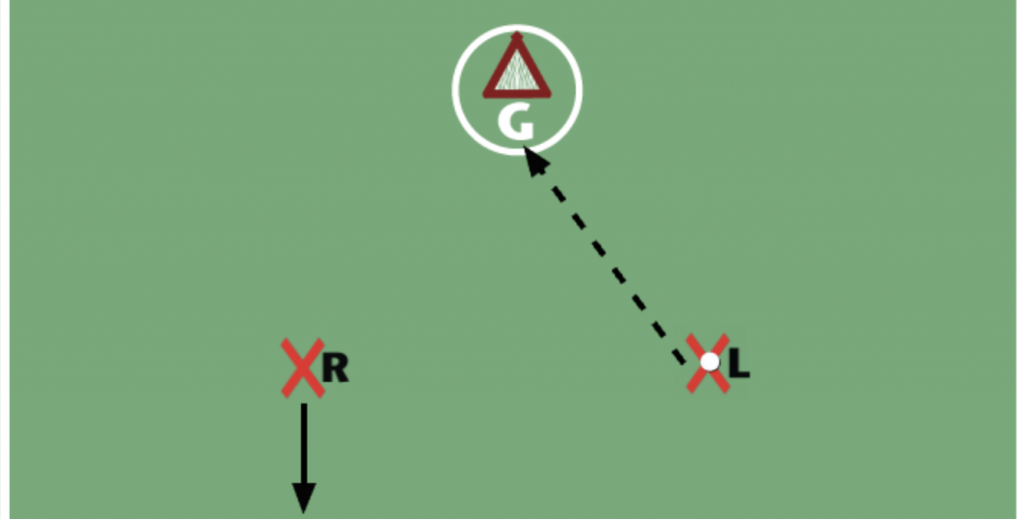

In general, the rule in box lacrosse is that the highest player on the off ball should be covering the reverse transition if there’s a shot from the opposite side of the floor (see below)...

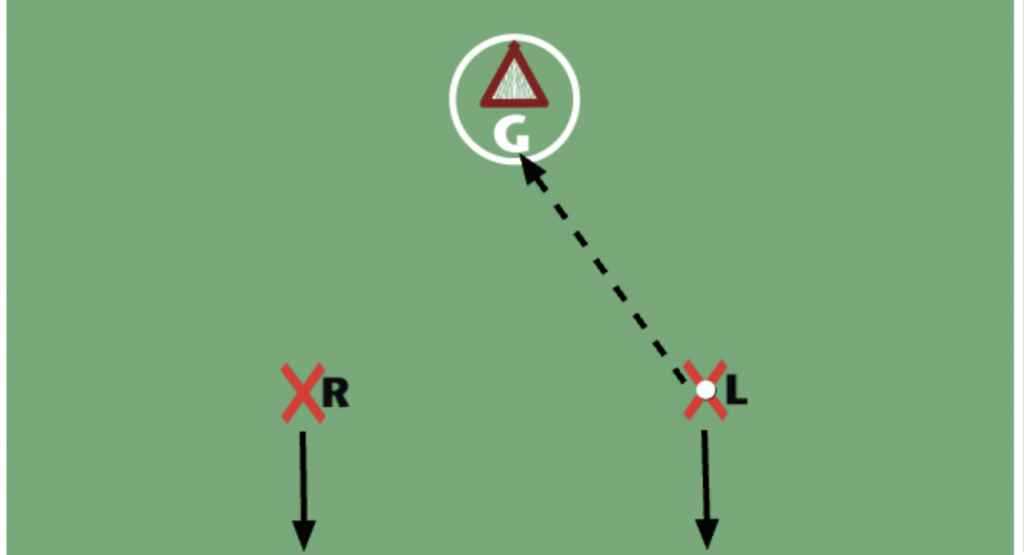

If the goalie makes the save and secures the rebound, both high players on offense should be getting back and not letting anyone behind them (see below).

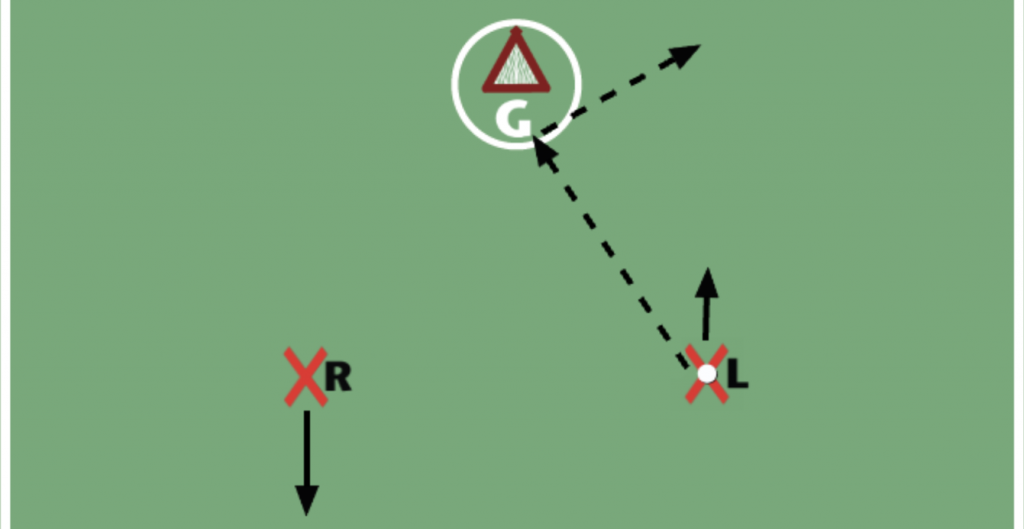

On a shot where there’s a rebound and a 50/50 loose ball on the same-side as the shooter, or a turnover on the ball-side, the off-ball high player should be getting back on defense and the on-ball high player needs to decides either to attack the rebound or get back, depending on the situation (see below).

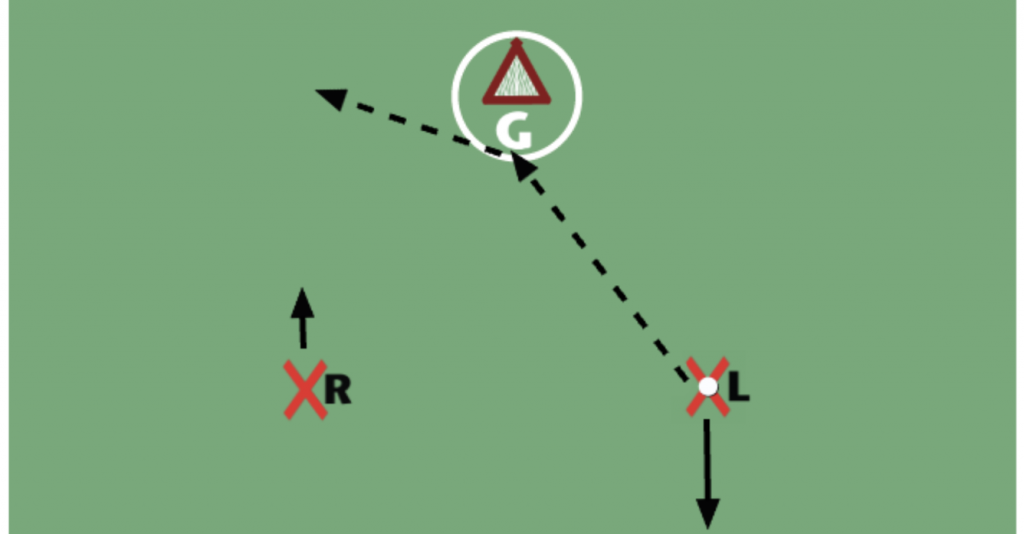

On a shot where there’s a rebound and a 50/50 loose ball on the opposite side as the shooter, the Off-Ball high player has to either attack the loose ball or get back depending on the situation; the shooter should also be getting back.

Clip #2 (Canada - Defensive Set #2): “Currier Good Show Of Help”

In Defensive Set #2, Byrne #22 was low and stayed tucked in this time, which ultimately worked out better than being pushed way out on the last clip. The Americans liked to swing it once around and attack from the opposite shooter position, which was a common theme for most of the game. Again, we have another good “show” of help by Currier, which forces #26 Schreiber (Former NLL MVP and 3x PLL MVP) to turn back and basically take an alley shot on his non-dominant hand; which is a win for the defense every time.

Clip #3 (Canada - Defensive Set #3): “Alley Shot Leads To Another Breakaway For Currier”

As offensive motion develops with ball movement, defenders need to arrive at a check in control, never over-committing or over-checking, while keeping balanced. As the opponent gets closer to a threatening scoring area, the defender should be shadowing them backward towards the goal. Defense in its most basic form is a "numbers game," you are always playing percentages in a cat & mouse-like affair.

On the third defensive set for Canada, they should have switched before the alley dodge, #22 Byrne tries to recover but #14 Berg ends up sliding up field to try to get into the shooting lane and contest the shot. It ends up being a save and 3 Americans are caught low for a faux 2-on-1 turned partial breakaway for Zach Currier who makes no mistake for his second breakaway goal in the first 2 minutes of the game

Canada ends up taking a time out there next possession and here is a clip from McCardle in Huddle talking about needing to get back “get back” and cover “the hole”...also something about an alley dodge ;).

Clip #4 (Canada - Defensive Set #4): “Classic High/Low Switch From Canada”

The general team rule in a Helping “Man-To-Man” Defense is that the “high” defenders should always deny offensive players from getting over the "top-side." The "low" defender should always “funnel” low offenders upward towards the defensive help, while also denying getting beaten “underneath.”

In this next clip, Canada is still pressed out quite a bit low, with lots of Canadian defenders with their head on a swivel looking to help. You can tell the Canadians are communicating defensively, as this is the classic “high” low switch. #42 Petterson is telling #23 Rogers he’s got low, so when Tierney #3 drives underneath, Rogers just does an inside roll back into the hole, maintaining his “high” responsibilities (also notice #92 Smith helping in front and showing no respect for his check who is behind the net). Petterson continues to lunge out a bit, I’d like to see him sit back on his underneath responsibilities as he almost got beat here, but ends up coming up with the classic low-to-high trail check in the end. The USA player really should have just pulled it out like in their first possession, he had 2 other Canadian defenders ready to help even if Petterson did end up getting beat.

Clip #5 (USA - Defensive Set #2): “USA Not Doing The High/Low Switch Leads To An Off Balance Defense”

After a first “feeling out” type of possession that ended up as a turnover for the Canadians, here is the second defensive shift by the USA where you have the American’s not doing the high-low switch properly. Two guys end up jumping out at the ball resulting in the defense having to slide or rotate to recover, which ultimately throws the defense off balance and leads to a quality top-side sweep shot by Currier. This empty crease (“high post”) set-up on the weak side by the Candians would end up being the death of the USA. They simply had no answer, wanting to instinctively stay on everything instead of instinctively switching on everything, like the Canadian Help Defense. The communication between defenders should be to “stay” if it’s a bad situation to switch, otherwise, as communication breaks down with fatigue and other factors, the natural inclination should be for the defender to switch; not stay.

Clip #6 (USA - Defensive Set #3): “Lost Again In The High Low Switch”

Here it is again on the very next possession, both American defenders jumping out at the ball carrier off an east-west dodge off a pick. #1 Kirst tries to "stay" on #51 Jeff Teat but what he really needs to do is turn and clamp the picker; the other guy Tevlin #12 played it right and fired out. However, he likely never communicated how he wanted to play the situation and neither guy was on the same page about it. Kirst could have “stayed” on his check if the low defender communicated it to him, otherwise, you need to be ready to switch any time there’s contact on a pick; which I don’t believe was an established rule on this defense.

The low defenders have a greater responsibility for communicating picks than the high defenders, as they can see everything happening in front of them, as opposed to the high defender who has a harder time seeing what’s going on behind them. Beyond all else, communication amongst defenders for picks coming, when to “stay” on a check, and when to “switch” checks, is the key to a successful team defense. Players should constantly be talking to each other. A defender's head should be on a swivel at all times, allowing them to see picks coming from both right and left, and help where required.

Clip #7 (USA - Defensive Set #5): “Not Knowing Your Underneath Responsibilities”

Here we have a great initial set-up by the American defenders, in a “wall” with each defender a “step down and in” from the defender in front of them. Consequently, the high defender (#3 Tierney) tries to “stay” on teat as he runs down the side instead of passing him down to the defenders below him in “the wall” and maintaining his high responsibilities (the most important of which being not to get beat “overtop”).

#26 Schreiber is the low defender whose actual responsibility is to be there to cut off an underneath crease dive from Teat. If Teat wanted to check up and shoot at any point the closest player in the wall would then close the gap and get a stick on the shot (in this case likely the middle defender Kirst #1). Instead, it’s in the back of the net because nobody knows their job (the Americans aren’t used to playing with 5x5 short stick D).

Clip #8 (USA - Defensive Set #6): “Great On-Ball Defensive Positioning Less The Unnecessary Adjacent Slide”

This is actually great defensive positioning by the Americans, less one unnecessary slide towards the end. Here the on-ball defender (Kirst) is by himself (“alone”) and has perfect footwork, angling his feet to invite Byrne over-top where there’s help. The ball then gets swung to the righties, where the two defenders in a wall (low defender out farther then I would like), doing the opposite of the solo defender and with the low defender denying the top-side using their footwork and the threat of pushing their check into the crease if they try to go underneath. For some unknown reason the high defender (Tierney) slides down with an aggressive adjacent help slide and considering the low defender (Tevlin) did their job perfectly which this high defender needs to trust, he should only be providing top-side support not underneath support. A great second slide puts pressure on a wide open #14 Clarke Petterson, but there is no 3rd slide ready and unfortunately for Canada Petterson handcuffs #24 MacIntosh with the pass, who was alone in front.

Clip #9 (USA - Defensive Set #7): “Empty Crease: The Death Of The American Defense”

Here again, we have the “empty crease” set-up on the weak side. Again the low American defender on the weak side is not doing his underneath responsibility, which is even more vital than in Canadian box lacrosse, because in sixes you are allowed to full out crease dive through the cylinder. In this case, the low defender (#12 Tevlin) needs to show help underneath and “split” between his check and his help responsibilities. Elsewise, he needs to tell #26 Schreiber that he’s alone (“iso”) in which case Schreiber needs to deny the underneath lane by angling his feet on a 45 degree angle (like the beginning of the last clip) and forcing his check back over top to where there’s help. There was a big trend for players getting beat underneath late in quarters.

Clip #10 (USA - Defensive Set #8): “Can’t Forget About The Best Player In The Game!”

Lastly, a classic to do with not communicating well, #8 on the American Defense Adam Ghitelman (the back-up goalie!!!), literally had nobody this whole shift. #51 Teat is just sitting there completely uncovered the whole time. This is the type of stuff that happens late in quarters when guys are tired. One skip pass ends up being enough to force all of the defenders to slide and Byrne buries a set-shot five-hole bouncer, with authority. Five-hole seemed to be a very high percentage shot in this game, something which we will break down in our next blog on "The Canadian Offense."

So what’s the The tale of the tape? Speaking to just the first quarter, Team USA did not have a single fast break (odd player break) the whole quarter - 5-on-4, 4-on-3, nothing and in fact they only had one the entire game. There’s also no excuse for not knowing your responsibilities for covering against fast-breaks by the opponent, this was very evident at the previous year’s Super Sixes. A 2-on-2 in the open field is like a 2-on-1 in box lacrosse, in terms of the type of quality shot you should be able to get in that scenario.

Outside of transition goals, Canada scored about half of their remaining goals over-top and half underneath in terms of goal distribution, whereas the US seemed to favour the underneath action. 3 players got beat for goals underneath on 3 attempts in the 1st quarter between 5:20 to 1:45; zero on zero attempts in the 2nd quarter. 3 guys get beat underneath in a row late in the 3rd quarter (2 for goals) from 2:13 to 1:08, which is when players are tired and the communication ceases or at least slows down. Canada was 1 for 1 in the 4th quarter, scoring an underneath goal on the very first goal of the quarter (blood pooling in legs at quarter time, lactic acid building up???). Another reason there was only 1 underneath attempt in the 2nd and 4th combined, could have been the distance of the changes (“long change”) and guys perpetually getting stuck on the field. However, if you can identify a “pigeon” as we call them, someone who is stuck exhausted on defense, it would still be a great opportunity for a fresher player to try to “iso” them at the crease.

The final key to the Canadian success was their ability to get to the middle (see “crease walks”) and keep Team USA out of the middle, which is something I will give you more of a visual on within the sixes offensive blog.

Aside from how goals were scored I would also love to know how many goals certain players cost their team defensively, like the proverbial “transition player” who gets you one goal per game but costs you two. However, that would be beating a dead horse at this point. It would also be interesting to know who is covering the most ground out there in terms of how far and how fast they are running, which is something we will look at in the upcoming “science of sixes” blog.

The bottom line is, whatever you are doing out there you are best to err on the side of defense and always be thinking defense first! Also, be able to push the reset button quickly, as there’s less time to reset mentally in 6’s and the “next play” is already happening before it even begins.

To view the full Vlog related to this article please visit our youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IwWh5iYnJsc&t=43s

0 Comments