Sixes Lacrosse: The Science of Sixes

In this blog we will discuss the science behind the cardiovascular requirements to play sixes lacrosse and how they differ from box and field lacrosse, as well as the art (science?) of picking your team based on those physiological requirements; alongside skill requirements.

Let’s start by looking at the differences between the Canadian, USA and Haudenosaunee rosters from the 2021 Super Sixes tournament versus what they put out on the field at the World Championships in 2022 in Alabama.

Looking first at Canada, having spoken with one of the team management personnel, he told me outright that 2021 was essentially a tryout and experiment for 2022. What was the experiment? It was whether to pick offensive/defensive specialists and how to use them, versus utilizing the proverbial two-way (transition) player. From the 2021 roster you see below only 3 “offensive players” made the 2022 team: Clarke Petterson, Jeff Teat and Dhane Smith; alongside 3 “transition players” Josh Currier, Bryan Cole and Reid Bowering. If you look at Canada’s 2022 roster, in the end there were 5 “transition players” and 5 offensive specialists. The players who didn’t participate in 2021 who made the team in 2022 were: Josh Byrne & Wes Berg (Offensive Specialists), as well as Challen Rogers & Jordan MacIntosh (transition players).

What does this suggest? Despite having impactful offensive production in 2021, offensive specialists like Mark Matthews, Kevin Crowley and Ben McIntosh all didn’t make the 2022 roster. Despite 2 goals a game on average, it wasn’t enough to secure a spot on the roster. Ryan Lee wasn’t there in 2022 either, however, that was due to injury; Dillon Ward also wasn’t there because of an injury sustained in the PLL; Dyson Williams because of school commitments.

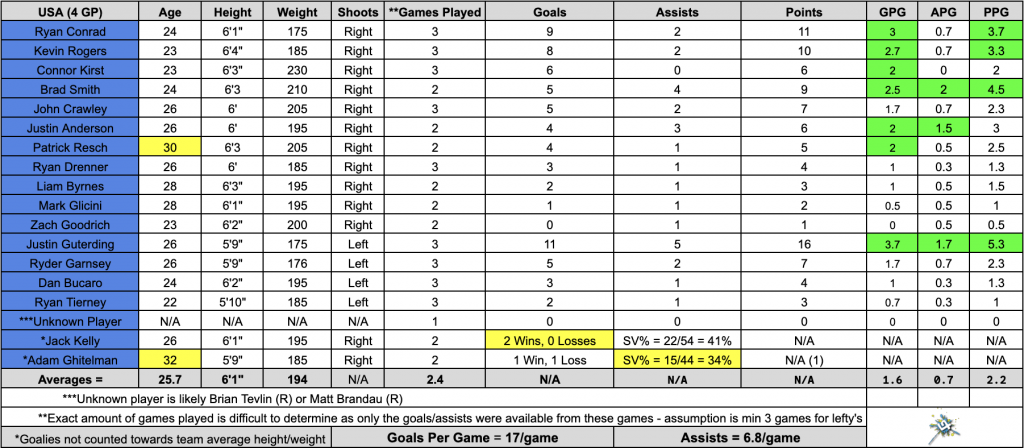

Looking next to the Americans, from the 2021 roster you see below 6 players (+ both goalies) made the 2022 team: Ryan Conrad, Connor Kirst, Liam Byrnes, Zach Goodrich, Justin Guterding and Ryan Tierney. The 4 players added in 2022 were: Tom Schrieber, Matt Brandau, Brian Tevlin and Colin Heacock. Interestingly, Brad Smith and Ryder Garnsey were the only two “attack” or offensive specialists at the 2021 tournament and neither of them made the roster in 2022. It makes you wonder when the last time these guys ever played any defense was, as at least box lacrosse offensive specialists have to run back and play defense a couple shifts a game. All players on the USA 2022 team are listed as midfielders in the PLL.

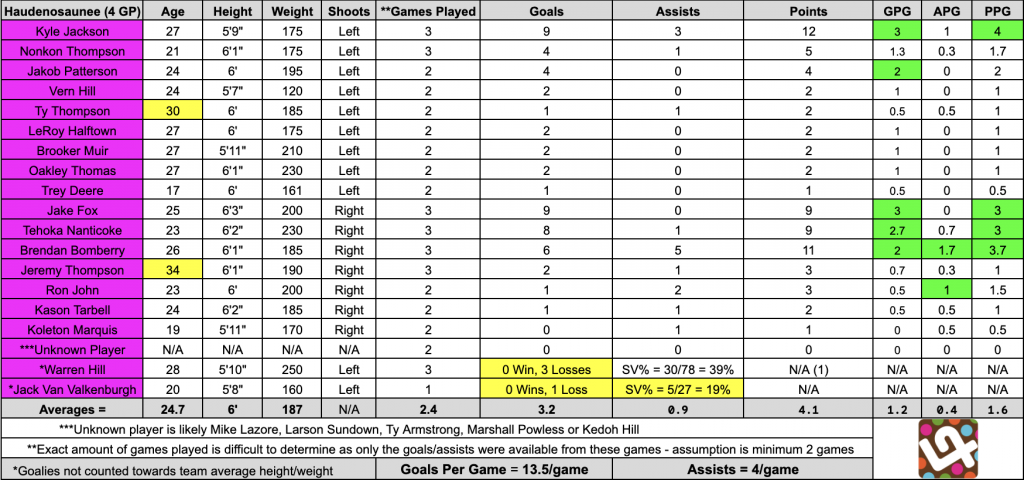

As for the Haudenosaunee, from the roster you see below all players that made the team in 2022 were there in 2021 except for one, Cody Jamieson. Cody took the place of the backup goalie Jack Van Valkenburgh, who got lit up in 2021 with an abysmal 19% save percentage. The 2022 Haudenosaunee roster contained 3 “offensive specialists,” in Kyle Jackson, Jake Fox and Jamieson, with Fox and Jamieson having very mediocre production at the tournament. As I mentioned in my “Defense Wins Championships” blog we know nothing about how well they did on the defensive end, outside of anecdotes.

The consensus seemed to be that sixes lacrosse is a young man’s game. The Haudenosaunee were considerably younger in 2021 with two teenagers on the roster (as well as a 20 and 21 year old). However, in 2022 the average ages on each team were: Canada 26.8, USA 26.3 and Haudenosaunee 27.2. If you consider that a man’s physical prime is between age 26-30 (with a 1% average decrease in muscle mass until death), it makes total sense. If these teams were thinking ahead to 2028 and the possibility of Olympic Inclusion, then perhaps it would have made the most sense to bring a roster of 20-24 year olds, as they are the ones who would be 26-30 in 2028. However, undoubtedly everyone was competing to win in 2022, with no guarantees for 2028 at that point. Likewise, the majority of 30+ year olds still ended up getting cut from 2021 to 2022, for one reason or another.

Is a 30+ year old with upwards of 10 years of professional lacrosse experience as hungry to continue training at an elite level as a 20+ year old with lots more to prove? Not likely. There are a few exceptions, but when you factor in full time work outside of lacrosse and young families to take care of, the job of remaining in tip-top shape gets harder from year to year as you enter your 30’s; I say this from experience.

One of my biggest competitive advantages as a player and one of the main reasons I made it to the NLL was because of my knowledge and understanding of the strength and conditioning requirements to play box lacrosse at the highest level. Having graduated in kinesiology and going on to obtain a CSCS (Certified Strength & Conditioning Specialist) title, I am technically one of a handful of people in box lacrosse to truly understand the sports science of this discipline of lacrosse.

As a career bubble player who was in and out of the line up, I wasn’t there because of my skill per se, it was the intangibles. Shut down defense, loose balls, toughness and strength and conditioning was my game, in all reality. I always came into training camps a step ahead of the rest and dominated in the physical testing components of camp.

One of the other things I did as a bubble player was make the best use of my time when I was out of the line-up. One game I studied an elite offensive player (Casey Powell) and another an elite defensive player (Jeff Moleski) to chart their average/median shift lengths and recovery periods. What I found was that the median shift length of both players was 25 seconds, with a median recovery (rest) period of approximately 50 seconds (a 1:2 work:rest ratio), with every 3rd shift having an extended rest due to TV timeouts, regular time-outs, injuries, etc. Total shifts were 49 per game. These are the conditioning intervals I used for training for box lacrosse for the remainder of my career and to this day when I train/coach my athletes.

Where the actual science of training for lacrosse is a very broad subject, I will focus on the conditioning of Sixes for the remainder of this blog. The first thing to appreciate is that with only 10 runners on a roster generally speaking (unless you are like Haudenosaunee and go with 11), the work:rest ratio in Sixes lacrosse is 1:1.

You can see why teams wanted “transition players,” used to less rest and longer shifts than the rest of the NLL/PLL players. As the Americans were primarily midfielders in field lacrosse, they would be more used to longer shifts and playing in both ends than the majority of NLL players. However, field lacrosse teams often have 4 lines of midfielders, bringing their work to rest ratio into the 1:3 range, allowing for much more time for complete rest. In a 1:1 work to rest ratio, players are often hopping back out onto the field with “incomplete rest” bringing them deeper into the realm of what we would call HIIT training (High Intensity Interval Training).

The other consideration is opportunities for rest when you are on the floor/field. In box lacrosse, the old saying goes, you should always be running when you are on the lacrosse floor (something which we hold in esteem in practice as well). In all reality, you might have a brief 2 seconds here or there where you are relatively stationary, perhaps able to take the opportunity to take a few deep recovery breaths while on the floor (many players don’t even know how to do this). In field lacrosse, especially when there’s no shot clock and with all of the around the horn action they do before actually attacking the net, the intensity while on the field is much less than box and the opportunities for informal rest on the field are much more frequent. If you look at attack and defensive players, they barely even enter considerable states of fatigue, not needing to work on their anaerobic capacity like the midfielders, or offensive/defensive specialists in box lacrosse.

Despite a game of sixes lacrosse being half the length of a regular box lacrosse or field lacrosse game, the relative workload and specifically the aerobic power required to play are substantially higher during that time. World lacrosse reports that the average distance covered in a Men’s field lacrosse game is 2436m vs. Sixes which is 2384m, again in half the amount of total time. That translates to 209m/minute in sixes lacrosse versus 172m/minute in field lacrosse.

How does this look in a practical sense, when it comes to training for Sixes lacrosse?

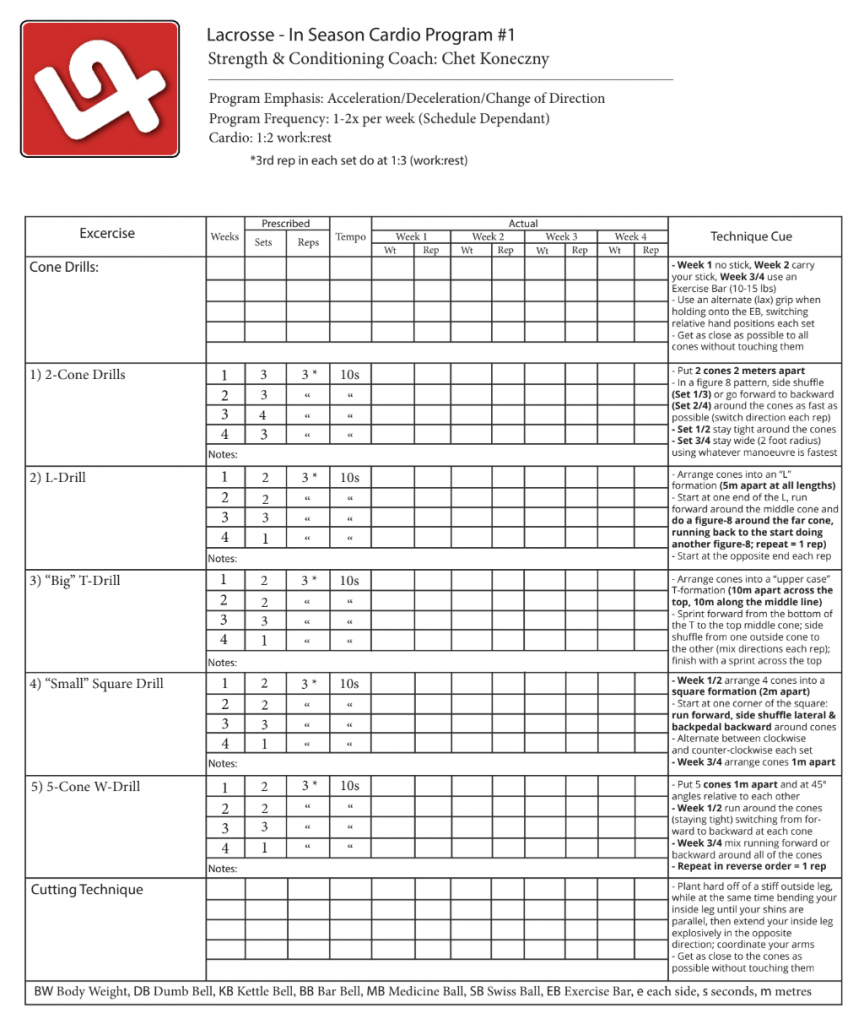

Below is program 1 (month 1 of the season) of an in-season anaerobic conditioning program (and video to follow) that I used to do for box lacrosse at a 1:2 work to rest ratio, as mentioned. Each drill takes approximately 10 seconds to perform and therefore in order to stay in line with a 1:2 work to rest ratio, the athlete would then take a 20 second rest before they perform their next rep through the drill. There are 33 total reps of 10 seconds in week 1 and by week 3 (the highest volume week) there are 48 reps of 10 seconds. Remember the total shifts that Powell and Moleski had was 49.

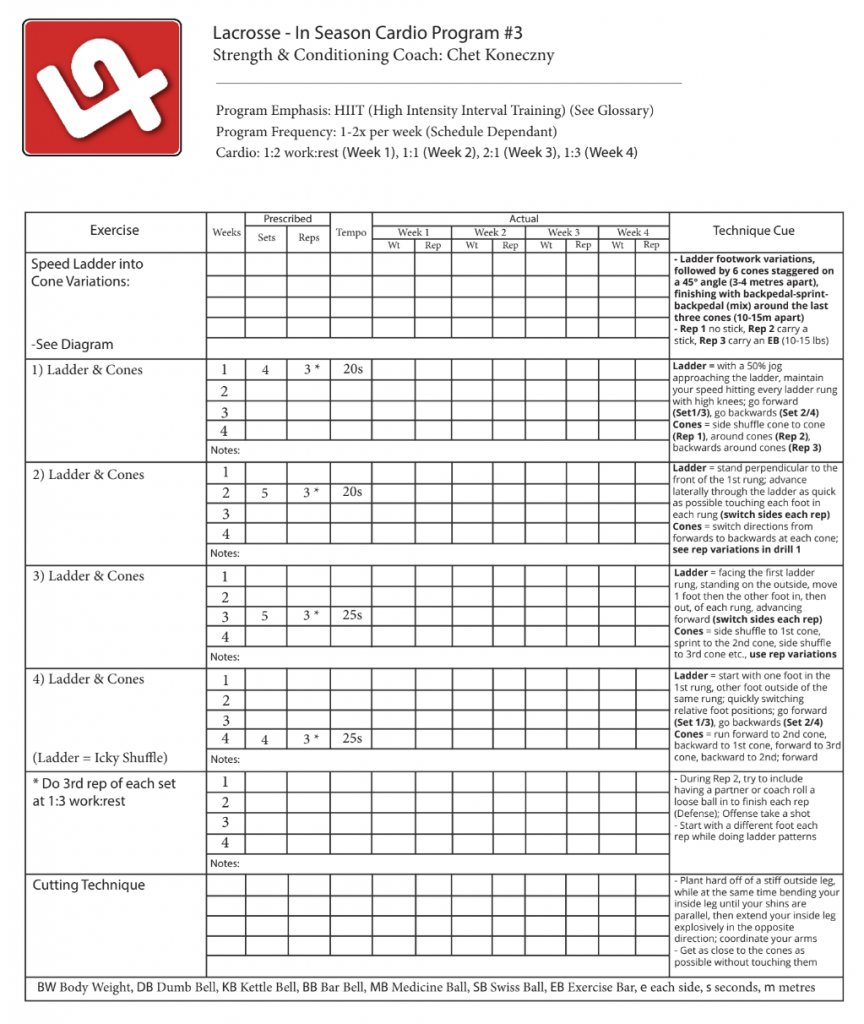

Building up from program to program, by program 3 (month 3 of the season) each drill takes approximately 25 seconds to perform and therefore in order to stay in line with a 1:2 work to rest ratio, the athlete would then take a 50 second rest before they perform their next rep through the drill. This is what they do in week 1, for 12 reps, which in all reality is only the equivalent of approximately one quarter of an NLL game. However, the intensity increases in week 2 and week 3 when the athlete is asked to complete reps at a 1:1 work to rest ratio and later a 2:1 work to rest ratio. Week 2 and Week 3 is performing what is known as HIIT (High Intensity Interval Training) and for box lacrosse would be a form of “special endurance” where a player has to “double shift” for instance, which is much more common for offensive specialists than defensive specialists.

Sixes lacrosse arguably has an average shift length of 50 seconds, which was the average combined defensive and offensive shift in the NLL when I did my study. That also means that players have roughly 19 shifts on average per game in sixes lacrosse, if you divide that by the total length of the game, which is 32 minutes (running time). So these HIIT intervals for box lacrosse shown above, being performed at 1:1 work to rest ratios, are actually just the standard ratio for sixes lacrosse. HIIT intervals for sixes lacrosse would thus need to be done at the 2:1 work:rest ratios, although a strong foundation of 1:1 work:rest ratios should be built before venturing into these types of high intensity intervals. In fact, in off-season training for box lacrosse, or sixes in this case, players should actually build a strong aerobic (continuous “steady state” cardio) foundation, gradually transferring to majority in anaerobic (sprint) training by the time they reach the season. This allows for optimal recovery when resting.

Having now superficially broken down cardio training considerations for box and sixes lacrosse, the fact remains that two-way players that are capable on both sides of the ball, alongside offensive specialists with defensive upside, are the ideal players to make a team in sixes lacrosse. All must be in superior cardio-vascular shape. Players that are in their athletic prime, ages 26-30 years old come the 2028 Olympics, are the most likely to make up the core of the best teams at the tournament. Other countries attempting to qualify are best to take note and start focusing on the sports science of lacrosse if they hope to compete for a spot on the big stage; the same for those with medal aspirations. This science is not just to do with cardio-vascular science, which team Japan clearly exemplified in their monumental bronze medal win in 2022, but also with injury prevention, the development of sport-specific power (via resistance training & plyometrics), mental performance, team cohesion and further with the technical/tactical development of box lacrosse skills and systems.

0 Comments